Competing Visions of What the West Stands For

This year’s Munich Security Conference put the state of the transatlantic alliance under a harsh spotlight. Senior officials from the United States, Europe and Ukraine gathered for three days of talks, but beneath the formal speeches lay a clear divide over what the West represents — and where it is headed.

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio argued that Western civilisation is in decline by choice and needs to be revitalised. He said Washington has “no interest in being polite and orderly caretakers” of what he described as a fading status quo. While his tone was less confrontational than last year’s address by JD Vance, Rubio’s message was similar: Europe and America must correct policies he linked to unchecked migration and climate orthodoxy.

Yet Rubio also stressed that the United States sees itself as deeply tied to Europe, calling America a “child of Europe” whose destiny remains intertwined with the continent.

That narrative was swiftly challenged by the EU’s top diplomat, Kaja Kallas, who rejected the idea that Europe is decadent or in need of rescue. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said she felt reassured about transatlantic ties after Rubio’s speech, but the tension in tone was unmistakable.

Ukraine and Europe’s Role in Peace Talks

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy used the conference to voice frustration over Europe’s limited role in U.S.-brokered peace talks with Russia. He called Europe’s absence from the negotiating table a “big mistake,” arguing that the continent’s security is directly at stake.

Although European nations are now the largest providers of military and financial support to Ukraine — and are expected to shoulder most post-ceasefire security guarantees — they have been largely sidelined diplomatically. French President Emmanuel Macron has attempted to reopen channels with Moscow, but with little visible progress. Lithuanian President Gitanas Nausėda bluntly suggested that Moscow is unwilling to engage with Europe while Washington allows that dynamic to continue.

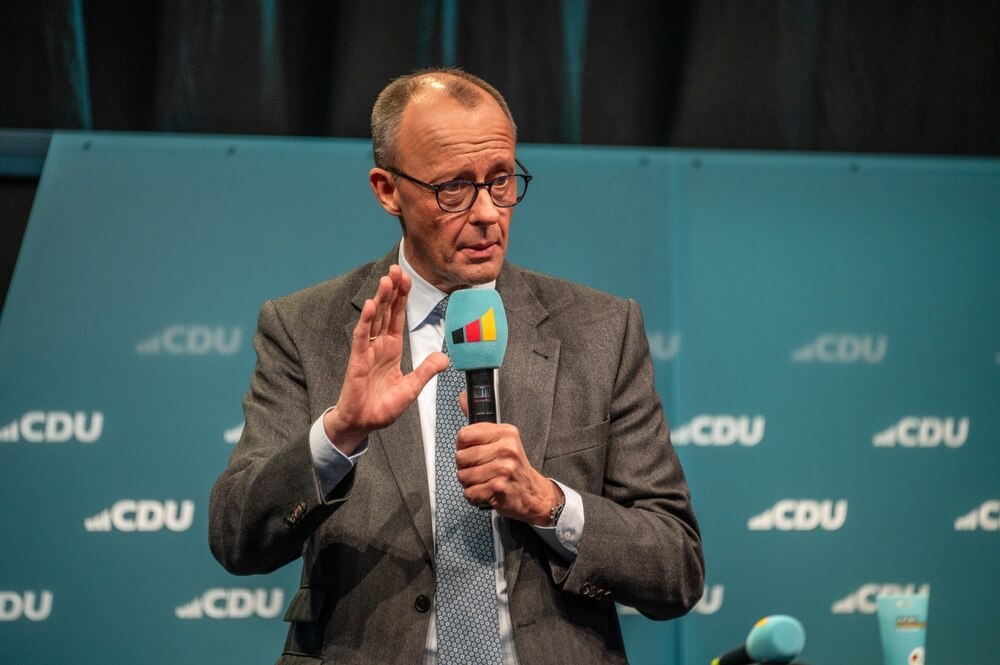

Meanwhile, Germany’s Chancellor Friedrich Merz warned that the post–World War II rules-based order “no longer exists.” He argued that an era of raw power politics has returned, and that Europe must show determination if it wants to safeguard its freedom.

Nuclear Questions and Arctic Tensions

Security debates extended to nuclear deterrence. Macron revealed that France has opened a strategic dialogue with Germany and other partners about how its nuclear doctrine could contribute to Europe’s broader defence posture. The discussion reflects growing uncertainty about the long-term reliability of U.S. protection under NATO.

Not everyone welcomed the idea. Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez warned that nuclear deterrence is an expensive and dangerous gamble rather than a guarantee of safety.

Tensions also flared over Greenland. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said U.S. interest in the Arctic island has not faded, despite recent diplomatic efforts involving NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte. Frederiksen made clear that Denmark’s territorial integrity is a “red line,” while Greenland’s Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen described external pressure as unacceptable, even as he reaffirmed Greenland’s commitment to the alliance.

Von der Leyen closed the conference by calling for the EU’s mutual defence clause — Article 42(7) — to be strengthened and made operational. With an €800 billion push to bolster defence capabilities underway, Europe is clearly preparing for a more uncertain world.

If Munich revealed anything, it is that while the West still speaks of unity, it no longer speaks with one voice.